Blog / 27 December 2025 / By: Cat Valentine

Cat Valentine Blog: Bassnotesonhope X-Mas Gig

Cat Valentine takes us down a magical mystery tour of a flatshow in Kilburn, writing up the wisdom of bassnotesonhope, a choir-band of ‘naive socio-geo-political’ inspiration.

If it takes a village to raise a child, it took a global village to raise these beautiful singing children in their twenties, and an Abby Lee-Miller-esque level of determination to rally them into performing. Melodia’s flat hosted the line-up: Charlie Osborne, Bassnotesonhope, WorldpeaceDMT, Floods in Atlanta.

Beaming into the instagram live at the party of dreamers, last night we blurred the line between audience and actor… last night was an episode of Dance Moms…

I’m Cat Valentine, member of choir-band bassnotesonhope. This is my report on the second gig we ever played.

"Almost as if it was just a random houseparty filled with people who, full-time or occasionally, dream of being rockstars."

It was a Christmas show put together by Leo (WPDMT) after he asked on his IG story if anyone had a free house to host. From what I understood, a random kid responded by offering up his mom’s house (without permission) while she was away, under the condition that he could play the opening set. He was in strict charge of the RSVP list and neighbours weren’t a concern of his. I pictured some kind of underground-music-loving Cartman figure who would force us into listening to some awkward set for half an hour.

On the night of, when my Uber dropped me off in residential Kilburn I was kind of stranded with all my instruments for a while. I couldn’t really Google Maps my way to the house, but slowly I started noticing e-girls and hediboys flocking around here and there, so I knew I was getting warmer. They approached me kindly, asked if I was playing, and then offered to carry my instruments and help me find my way. I remember this guy Harry who carried my keyboard—shoutout to you, Harry, if you read this. My bandmates were waiting outside and we all went in together, saying thank you and see you later to the cute e-girls and hediboys, who were made to wait until the “doors” officially opened.

Inside the house I realised that me and my band members were basically one third of the total capacity of people who could fit in this flat. As I was daydreamin about the problems the size of our band will cause for the future shows all over the world we hopefully one day get to play, the “kid” whose house it was walked up to me and asked if I was “Cat.”

“Yes, I am Cat Valentine. Is this your house?”

I was a bit surprised. Turns out the random “kid” wasn’t a random kid but a guy with a music project called Melodia. The house was his and his bandmates’ flatshare.

They opened the night with a cool set. One of them played electric guitar and sang in a nice, vulnerable way; the other played bass guitar using a violin bow. With the exception of Ike and Leo annoyingly having a vain photoshoot throughout most of the set, everyone else was locked in, sitting on the floor subtly head-bumping. To me it felt like being somewhere in between that trancey listening-party space in Berlin—where everyone lies on the floor listening to a set that’s oddly quiet because it’s in a residential area—and what I imagine it must’ve been like (idk, I can only imagine, I was personally a high schooler in Amsterdam at the time) to attend a Double Virgo gig when they were just starting out.

After Melodia it was Charlie Osborne’s turn. She prepared poetry and read it to a score of her friend Eric playing banjo. Charlie’s voice sounded soft and beautiful, and Eric’s banjo playing took me to a fictional place. I sometimes long for: an American road trip in an America I imagine from a YouTube clip of Townes Van Zandt playing Waiting Around to Die, every spaghetti western I’ve ever seen, and the movie My Own Private Idaho.

At this point the living room was so packed I could barely see anything, but for a brief moment I caught them sitting on the floor with their backs against each other, looking magical.

Then I had to gather my troops. We were on next. I found some of them mid doing a line, some doing vocal warm-ups in the toilet, some doing final touch-ups on their costumes. I felt like Abby Lee Miller, losing my shit about choir members losing their stage props and not knowing the order of the setlist (JOJO, HAVE YOU LEARNED NOTHING?!).

Abby Lee Miller is a good analogy here actually, because bassnotesonhope takes inspiration from naive socio-geo-political themed children’s musical, theatre, and dance recitals.

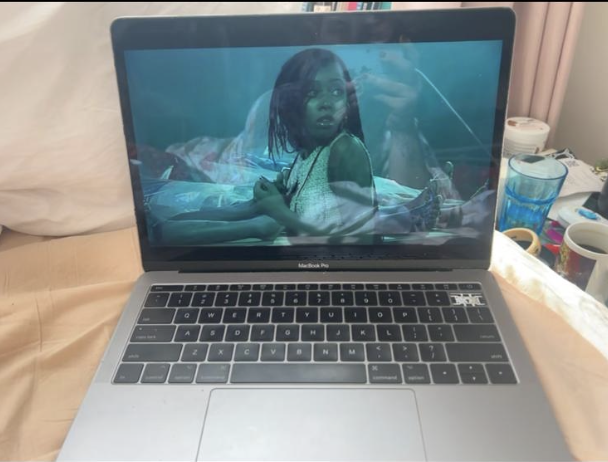

Think Dance Moms season 3, episode 12, when they prepared a dance recital in honour of Rosa Parks, and for a moment the role of Rosa Parks was undecided between Nia (the obvious choice, as she

was the only black girl in the group) and Kendall (a cute white girl with an overbearing mom who calls her “My Little Kendall,” which on TikTok has now granted Kendall the nickname MLK). In the end Nia got to be Rosa Parks, but Kendall will forever be MLK.

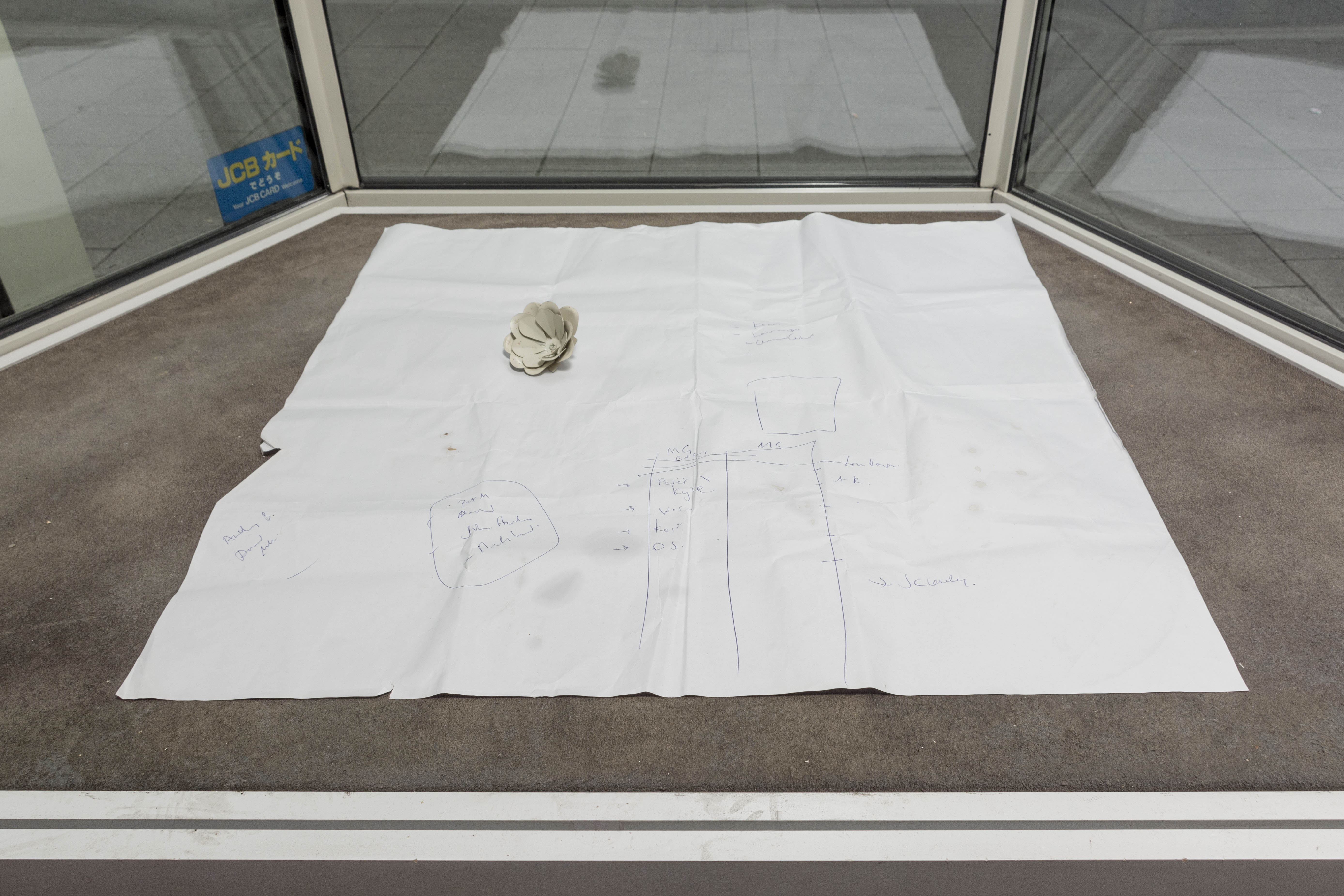

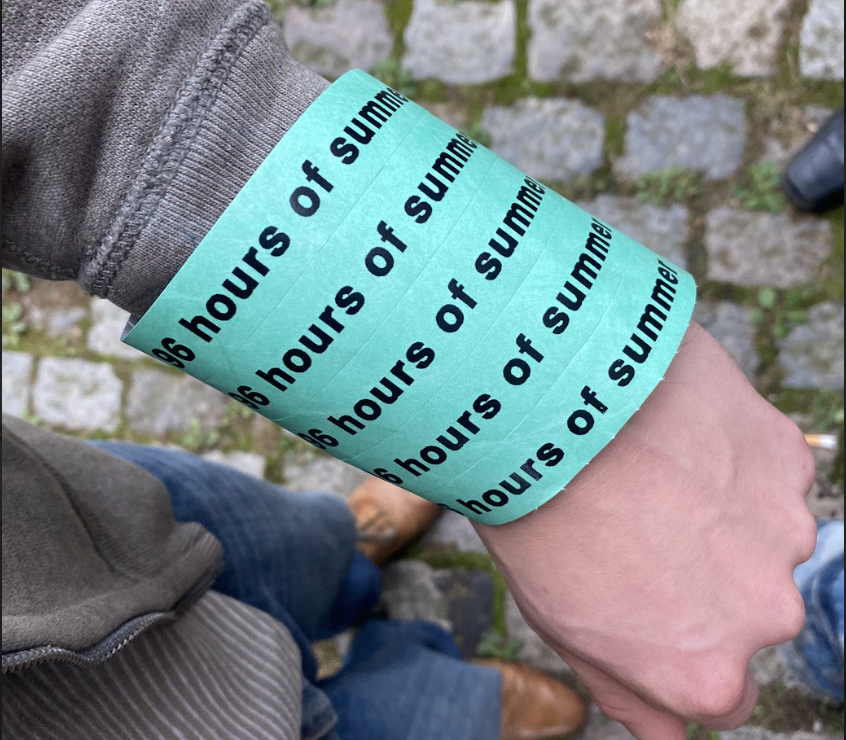

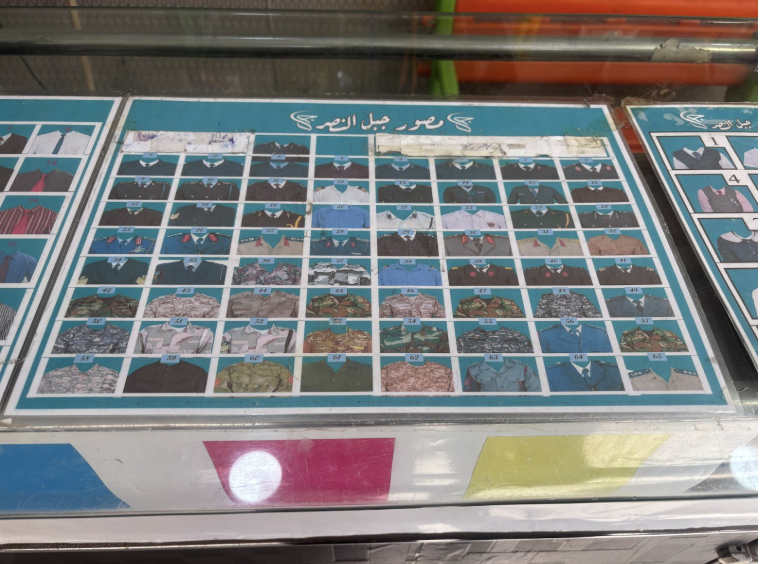

For the Christmas show we prepared a set in honour of Somalis and their right to return to their promised land: Minnesota. If you’re a reader who doesn’t understand what I’m talking about, I’ll briefly explain these geopolitics to you. There’s a large Somali community living in Minnesota. Some of them kinda don’t really integrate in the way certain Americans want them to, prompting Trump to talk a whole lot of shit about Somalia during a press conference. Somalis responded to this by rage-baiting Americans on X and TikTok into believing that they think “The Minnesotas” were promised to them in the Old Testament 3,000 years ago and that they’ll soon be mass immigrating through birthright trips to the promised lands. Bassnotesonhope stands in solidarity with the Somalis. Bassnote memberMartyna read a short text describing how Somali explorers found Minnesota 3,000 years ago, followed by a choral version of Coming Home (not the P-Diddy version—strictly Skylar Grey).

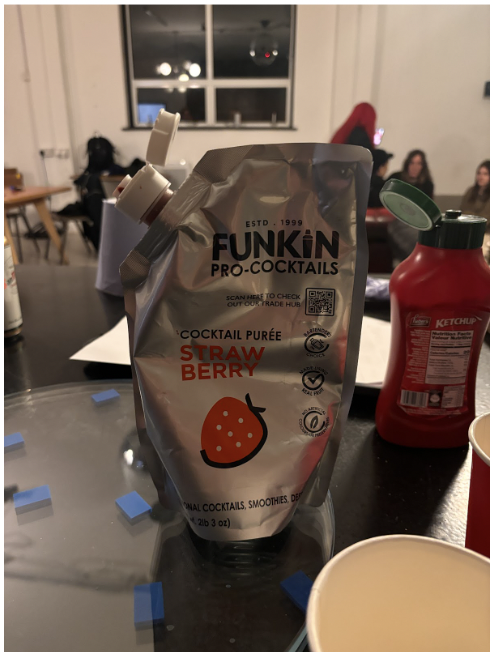

Choir member Bexley came up with the idea to sing from the perspective of Americans welcoming Somalis into Minnesota, so we sang Glad You Came by The Wanted.

We closed with Homemade Dynamite by Lorde, aligning ourselves with peoples worldwide forced to fight back against oppressive states and regimes through guerrilla warfare whether online or IRL.

Our set flew by, and then it was time for the headliner: WPDMT. Rowan Please looked phenomenal.

She’d painted her face and had been painting other people’s faces throughout the night to raise money for the homeless. I briefly spoke to her manager, who had a blue butterfly painted across his face, which was very cute.

Everyone—WPDMT member or not—was singing along or playing some kind of instrument, receiving soft instructions from Leo. When they played Year of the Dragon, an acoustic version of a Bassvictim song, Maria M put a phone in my hands.

“We’re live on Bassvictim. Record.”

I recorded the whole thing, and afterwards we realised the sound had been off during the live.

“I DON’T FUCKING HEAR ANYTHIIIIIIING” a Bassvictim fan commented.

So we did the whole thing again, sound on this time. After that I requested Love Yourself. They played it. I loved it. At that point everyone was just yelling stuff. Someone yelled Beatles! Across the Universe! so we collectively played Across the Universe. Chords kept being played, people yelled random phrases, and out of that the beginnings of a new song were written: Bassnote member Isobel’s line "All of our loser neighbours... can’t stop us from dancing....” spun into a twenty minute jam session, which ironically caused the neighbours to complain massively and then the party was shut down. Unfortunately Floods in Atlant last on the lineup, didn’t get to play his set.

I was asked to review this night, and I don’t think I can objectively do that, since I was part of it. But if I try anyway, and be as ruthless and critical as possible, I’d give it a ten out of ten—because it was fun, DIY, and collaborative in a way where the boundaries across acts, audience, and performer completely disappeared.