While thankfully less common than in Berlin, a city replete with smoothened, outsourced objects often mistakenly seen as the end of thoughtful conceptualism rather than as the product of a much lower common denominator—a Ringbahn-bound collective condition of smooth-brained apathetic “coolness”

conceptual art in New York can at times feel like a circle jerk for bisexual men whose flirtations with the same sex are limited to the moments of tantric, pseudointellectual foreplay they partake in at downtown openings.

At Maxwell Graham, a merely aesthetic or self-aggrandising relationship to conceptualism has always been out of the question. While some of the gallery’s roster admittedly does less for me than the work of, say, Hamishi Farah, Ser Serpas, Cameron Rowland, and Tiffany Sia, there is little of the juvenile “I only got into conceptual art through Joseph Beuys” sentiment one often intuits in small downtown galleries. In “Display,” Zoe Leonard’s new exhibition at Maxwell Graham, comprised of only six gelatin silver prints depicting armor housed in nondescript museum and institutional settings, thought—the foundation of good conceptual work—is refreshingly at the forefront.

Much like the cold, detached hubbub sustained by the aforementioned men who sour conceptualism’s current reputation, the objects pictured seem as if they should foreclose sensuality or eroticism altogether in the way they privilege the episteme. And they do. Ranging between 300 BC - 1600 in origins, each piece of armor, even with its voluptuous tassets and faulds, is obviously masculine, immediately neutralizing the knowledge of the erotic, an arguably feminine power that Audre Lorde famously described as being often “misnamed by men and used against women.” Repeat those same forms multiple times within the same sterile vitrines, compositions, or gallery walls without providing historical context, and that repetition amasses into something more monumental: critique.

This is what Leonard’s practice does best—looking, repeating, serialising, aggregating to the point that form, always bound to history, begins to speak for things that transcend history. In the case of “Display,” what first emerges from this continuity of forms spanning 2,000 years in origins is the tired persistence of patriarchal militancy and violence throughout the history of the West—a fact that can be condensed into everything from the objects themselves, such as the muscle cuirass of the Romans and Greeks or the plate armor of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, to the rationalizing containers, such as the ethnographic, imperial museum vitrine, that precipitate their initial formation and absolve the sins that lie in their wake.

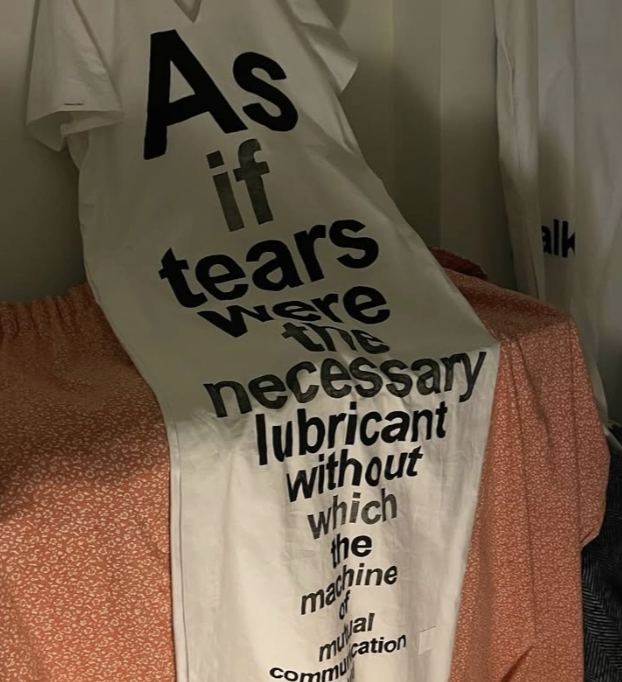

Leonard may share convictions with the mechanised, lens-based approach of the Düsseldorf Becher School, but her work is ultimately more aligned with the libidinal sleight of hand wielded by fellow queer conceptualists emerging in the late 20th century, e.g. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, David Wojnarowicz, Glenn Ligon, than any photography movement or school. Hence, the desire that still bursts out from “Display,” some of her most acerbically mundane work yet.

This rupture is concentrated in one photograph, Display IX (1994/2025), displayed on the wall directly behind the viewer as they descend the stairs to the main gallery dedicated entirely to photographs of garments used in war and feudal contexts. Having been initially confronted with images of statesque armour, frozen in mechanical movement, repeated, doubled, and pictured ever so slightly differently to the point that their historical idiosyncrasies are rendered moot, the act of turning around and seeing the broken ab-laden torso of a broken muscle cuirass depicted in Display IX (1994/2025) wrests the most powerful element from repetition’s grasp—difference. And with it, desire floods the scene, too.

This is hardly the same libidinal or auratic territory underlying Leonard’s 1992 text declaration on the occasion of Eileen Myles’ presidential bid that she wants a “dyke for president,” nor the critical erotics lingering in her early 1990s images of chastity belts, lifted skirts, anatomical models, and the Niagara Falls, or her late 90s images of urban trees breaking through the fences meant to enclose them. Indeed, the desire occasioned by the image of the broken muscle cuirass is more memetic and pornographic than it is erotic. After all, Display IX is still a picture of an object of war.

However, it is precisely because it resides in that unspeakable zone wherein war and desire commingle, that the image also tests the very bounds of acceptable desire, sex, and discursive practices—an equally abstract and material dynamic from which queerness emerges. Keeping with the photographer’s past work, this desire is not only theoretically gay, but empathetically so, in no small part because it immediately evokes the visual schema of Grindr, where one is most likely to stumble upon a naked, cropped, floating male torso today.

But surely one cannot outwardly express gay desire upon seeing the cuirass without entirely betraying Leonard’s searing critique? Leonard’s work somehow convinces me that both positions—the anti-war critic and the shamefully desiring subject—can be held at the same time, however delusionally. After all, the desire that breaks through this particular dusty vitrine is ruled neither by eros, nor agape, nor philia. It seeks release neither through sacrifice nor mutual destruction but instead mistakes the momentary mania of visual possession and pornographic arrest with the inexhaustible wells of the haptic and the erotic.

The cuirass, a form de-eroticised upon its moulded excision from the human body, already reached the artist broken and caged. She furthered this deadening process by capturing the fragment in black and white, transforming it into a fetishistic spoil of history in much the same way that ethnography, the progeny of empire pictured throughout “Display,” has historically relied on violent acts of photographic capture to fix culture as a fetish object as a means to keep it, study it, exploit it, be turned on by it, degrade it, and eventually dispose of it.

Like Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1924-), Aby Warburg’s unfinished project tracking the recurrence of classical images, gestures, and motifs across the history of Western art, Zoe Leonard’s practice often directs our gazes to histories that lie anywhere but the past. In “Display,” she pushes this to discomfiting ends, probing the psychosexual undercurrents of masculinist projects like war and questioning the latent biopolitical violence in 21st-century digital cruising (See the NYPD’s recent usage of Sniffies as a means to track and arrest cruisers at Penn Station) and the torso-directed desires it inculcates in viewers such as myself at even the most inopportune, or dare I say inappropriate, moments. At Maxwell Graham, the conceptual photographer first presents us with this sharp, Warburgian account of antiquity’s violent, pornographic “afterlife.” Then, she shatters things over our heads.