"Debtors and Daughters" A Longer Review of Tala Madani at Pilar Corrias

Essay / 2 February 2026 / By: Sean Steadman

"Debtors and Daughters" A Review of Tala Madani’s exhibition ‘Daughter B.W.A.S.M.’

A friend of mine recently joked that if art is to recover, it needs to bring back a punitive sense of shame. During the pandemic, a silent and collective surrender occurred. As billions in stimulus credit were pumped into the global economy, the last shred of embarrassment dissolved. Every artist I know periodically screws their face up in bemusement; they bleat out, “Why have things got so bad, so empty?!” For all the handwringing and punditry, the diagnosis is simple. This is what happens when a culture is in a lot of debt.

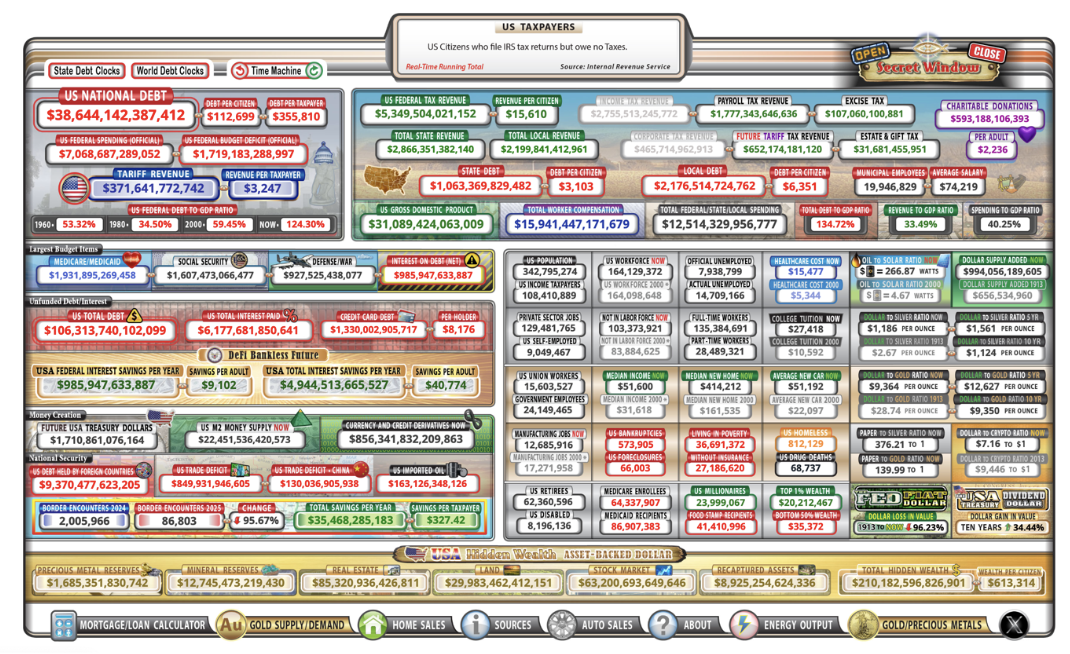

For half a century, access to cheap credit has left an overhang which is now at absurd levels: global debt is at 337.7 trillion USD. Art and culture, through both design and unconscious reflex, have become a blind scramble to prove society’s creditworthiness. In the FT last year, as Frieze 2025 opened, Tristram Hunt published a short plea article, “Don’t move to Dubai – this is still the place to be”, stating that “this month’s Frieze London art fair will prove that, despite Brexit, we are still a cultural behemoth”.

Screenshot of Live readout of USA National debt fromusdebtclock.org

Art has become a corporate culture. Corporatism is the administrative and disciplinary infrastructure of debt culture. Because art has no inherent utility, it relies on consensus to legitimise its monetary value. Therefore, art in a debt society, untethered from centralised patronage like the church or nobility, produces a priestly class of bureaucrats who toil to induce confidence in their investors, to prove their spending will pay dividends. Despite their antagonism, both Marxist-inflected art academia and market-driven dealers are debt-culture bedfellows. Both share the same impoverished ontology: art is reduced to an instrumental entity, stripped of any intrinsic or metaphysical good. Each leverages the financial precarity of artists to produce a ‘paper economy’ optimised for their respective pensions or bonuses.

Let me explain: The legalistic jargon of this unholy alliance is ‘critique’: a pidgin dialect that unburdens audiences from having an adversarial or individuated inner experience. Consensus over consciousness please! Critique facilitates growth: an expansion of customers.

To survive the desert of critique, artists, viewers and art sector functionaries are all expected to cosplay a sovereign intellectualism. After internalising the “problematics” of dirty money and hysterical moralism, admission to the tenancy of the ‘art world’ is granted. The more globalist the marketplace becomes, the more acutely artworks zombify into empty vessels, hollow enough to pipe critique-adjudicated stuffing into, the way custard fills sugary doughnuts.

Art has attempted to be industrial, but the bigger it grows, the less the audience cares. This expansionist corporatism seeks to maintain a numbed-out present; history and the future exist only to prop up the ‘contemporary’. Their proper function, which is to contest the present, is a taboo. This is because, in a debt culture, fear of the future’s insolvency is unspeakable. Thus, aesthetics taper into disciplined homogeneity, an amnesiac beige sludge. How quickly can we forget the next Marvel movie or faux Ab-Ex painting keeping collectors away from Dubai?

So be it. To the real artist, the above is of no concern. They are like the stringy marsupials after the meteor hit Chicxulub: against rational self-interest, they will go on making art. They do not have a choice; to be a real artist is both a vocation and a pathology. Furthermore, the artist must confront, and even love, the present, no matter how ghastly or petty it is served up to them. The pervasive death loop of preening nostalgia and vain nihilism is neither critiquing nor transforming anything.

This is why, standing in Tala Madani’s exhibition ‘Daughter B.W.A.S.M.’ at Pilar Corrias Gallery in London, I felt awash with relief at its humane agitation. The exhibition is ensconced in some prime real estate. Across the street on Savile Row is a lobotomised Nicholas Party exhibition at Hauser & Wirth; to the other side, a Bape store with hoodies slung over chromed mannequins with shark heads. The New Routemaster trundles by, designed by Thomas Heatherwick, one of the most egregious flunkies of the debt-nostalgia tundra. The barbarians are at the gates.

The exhibition is deliberately overhung, a spoofing of the locale perhaps, bait for the red-chip aficionados driving past in Lamborghinis. It is also a nod to twentieth-century conventions, into which the exhibition’s satire of technocracy and progress sinks its teeth. An army of gleaming cyborg women languishing in the loading bays of spaceships would be enticing for accelerationist crypto bros, were it not for the repeated accompaniment of humanoids of shit. As corporeal turds splash and smear their way down Duchampian staircases, reconstituted as gen-AI condominiums, the question arises: are the noble genres of satire and mannerism the most pertinent avenues available to painters at the present time?

Installation View of ‘Daughter B.W.A.S.M.’

Tala Madani has the admirable discipline of not fussing with her paintings too much. The surfaces are always fresh, zippy and erudite. In ‘D.B.W.A.S.M. (Teddy)’, the synthetic polymer panel surface has an embedded sparkle; a smoky figure is fumaged sub-dermally, accompanied by a dashed-off teddy bear in globs of lemon and chrome yellow. At times the paintwork is buttery and porcelain-like; in others, clunky. There is an enticing control: the audience gets pin-pricked as soon as they relax into carnal voyeurism.

As with all good satire, this is a humane display of both revulsion and attraction to the subject matter. Madani is wallowing in the muck whilst flinging it against the windscreen. Picabia and Duchamp both produced virtual erotic machines, their fantasy of sex deconstructed into vapours and pistons: a castrated kinematics. Tala Madani’s paintings invert this fantasy of bodiless bodies. They are ciphers of big tech: super-nervous crash dummies painted to feel stimuli which are usually pumped through their image, into the brains of a smartphone audience.

In ‘D.B.W.A.S.M. (Head Birth)’, two sister robots sit on a park bench, upright like Old Kingdom Egyptian figures. Their pregnant bellies blend from neoprene peach to swirling diarrhoea brown, eliciting a visceral sensation of pain. The shit figures and cyborgs interchangeably role-play children and parents, their fears and desires intermingling into a circular feedback loop, from tender intimacy to frantic desperation.

*Tala Madani D.B.W.A.S.M. (Head Birth), 2025 Oil and ink on synthetic polymer.

Detail of D.B.W.A.S.M. (Head Birth)*

The sex-meets-death fantasy of acquiescing into a perfect machine is potent. We are the ‘technological animal’ and desire ourselves as such. Narcissus loved his externalised avatar. There is no place more conspicuous than sexual reproduction, where the immaterial self is starkly contrasted against the machine of the body. For Madani, her maternal and debased figures are a kind of post-Hobbesian ‘body politic’. Gone is the masculine, pyramidal god-king, astride the ocean with sword and sceptre in hand, the masses within his chest cavity. The androids and shitty companions are a Beckettian reduction of the Leviathan into feminine sprites. The populist debt economy is hell-bent on depersonalising the body politic; it does this through an excessive pornographisation of political conventions. This produces an incel political appetite: the virtues of civilisation are converted into fetishes to be debased and exhausted for libidinal reward.

Frontispiece Detail of Hobbes Leviathan by Abraham Bosse

D.B.W.A.S.M. (Teddy), 2025 Oil and ink on synthetic polymer

Madani’s paintings function as cathectic amulets, much like the fascinus dick figurines of ancient Rome, welding together the animal body and eternal soul to ward off the influence of a corrupt polity. They are a warning: even if the axis of personal and political desire succumbs to a bleached sex-bot proceduralism – eros without a body – there will never be the libertarian fantasy of a society without society! New proliferations of disharmonious kinship will wriggle free and need to be arbitrated outside contracts and laws; intimate biological desire and revulsion will always be mixed into mass psychology. The holy subject of the mother and child, their conjoined self, refutes the toy-model democratic voter, utility-maximising creditor or sovereign bitcoin holder.

At the back of the exhibition, an animation of a sloppy turd figure imitates a woman from Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of figures in motion. This Shit Daughter/Mom jumps rope, waves a handkerchief and even embraces her human counterpart. Ghost-like, she is a premonition of the coming technological century, ready to haunt the sensors, CCTV cameras, and surveillance drones of modernity. The contemporary fantasy of neutral instruments replacing the mythic body is naïve. Humans desire their own destruction and hobbling, as Madani said in a conversation for the Vienna Secession in 2019: “Children eat their parents; they kill them with love.” With her painting, it is unclear who is biting chunks out of whom; it is a frenzy of mutual exhaustion. Catharsis is not an anaesthetic – it hurts.

So how does a society get out of debt fast? Mostly through innovation or stealing. Thus, we see Silicon Valley’s marriage to the military. Poindexter Google execs are made army commanders in a force which roams the planet, plundering fresh resources. Tala Madani’s work cajoles artists to get off their hands and knees, it asks culture the question, “Whom do you serve?” If it is not the ravenous golem within, then you are most likely an indentured servant in the bureau of debt.