"it's a fashion show, I think." Review of Bananna Karenina by The Pegram Collection and Alex Heard

Review / 9 December 2025 / By: Liza Minelli / ★ ★ ★ ★ ½

A review of "Banana Karenina" by The Pegram Collection and Alex Heard, which took place on a bridge in Archway last month.

I have 5 minutes at home to change into a dress adequately chic enough to fit my role as fashion show attendee. I am going to Bananna Karenina, a “performance featuring 9 dresses,” which will be staged on Sussex Way bridge, a no-where landmark vaguely in Archway.

To hold a show in public is to trust in the participants to behave when the hierarchy between audience and artist is removed. If vulnerability was hiding behind the texts of another man, the cracks in the lo-fi setting made the whole thing feel unassuming and human.

The show is a collaboration between artist Alex Heard and designer Mack Pegram, aka. The Pegram Collection. Described on Instagram as a museum in Buckinghamshire, a place random enough to blend into the brown and grey mush of Somewhere in England.

I make it to the bridge, where I am greeted by a horde of familiar faces I hardly ever get to see this far north of the river. The bridge overlooks a train track and I feel pride at recognising the reference despite never having read the book. Anna Karenina (1876) is one of those books that is so solidly book it feels you should have read it, haven’t read it, but probably really, actually have read it. It is like the bible, or Pride and Prejudice (1813).. If the railway was once a symbol of the modernising forces of industry, we now find them to be slightly ruined, going on as if they didn’t know how to stop.

People are holding pieces of paper and I. I want to get my hands on one. I ask someone where they got theirs, and I am interrupted by a youthful man in a suit who runs around the corner and emerges with a sheet for me. He is one out of two bow-tied servers carrying trays of water and wine. The servers wear suits for the very reason I am wearing my chic attire: servers wear suits.

Swooning music starts to play out of a boombox to my left, quiet at first and then loud enough to recognise it isn’t accidental and that the show is starting. The first model appears across the bridge. She is wearing a long and shapeless white robe, plain except for lines of black text which become legible as she gets closer. A friend speaks into a microphone and recites the text on the dress.

First, the front. Then, after the model turns, the back.

Though

Kitty’s

Toilette,

coiffure

and

all

the preparations

for the

ball had cost her

a good deal of trouble

and planning..

The next 8 models come and go similarly. The text appears in bursts of differently sized clusters, varying in dramatic and comedic effect.

Simple, natural, graceful - and, at the same time - gay and animated..

The words, ripped out of Tolstoy’s novel, are ready-made statements which have miraculously been given legs to walk on. No longer sitting next to Tolstoy’s characters, they can stand for everything.I feel that some of them are descriptors of the models themselves. Sometimes two words are placed together in a way that makes me laugh or seems to represent some distant truth that I know about the world. Or that I have been told I know about the world, and what our story is about, and how things go wrong, and so forth.

The models are styled in regency-era themed accessories: feathered boater hats, a basket of apples, twigs and other pastoral trimmings. An English re-reading of the novel’s original Russian setting. It’s 3pm on a Sunday in November and the sun is beginning to set over the bridge. When the music cuts in between songs, it is replaced by the rustling in the trees, the sound of wind blowing hair into the models’ faces and the fabric of their gowns in and around their legs, making it hard for them to walk. When the models pause long enough over the bridge, things seem still and I am tricked into feeling like everything fits and makes sense.

Families, lime-bikers and stray pedestrians are forced to meander their way through the obstacle course of cameras, speakers, and the bodies of former and current art students. One man, who looks smart enough to stage his own show, or has maybe gotten lost on his way east to join the other old and hatted eccentrics of London, is asking what this is all about – “it's a fashion show, I think.” A woman walks and runs as close to the edge of the bridge as possible, hoping to disappear into the brick, but this only makes the fashion-art-audience giggle harder. Others stop and will stay till the very end.

A man is filming the whole thing on his iPhone camera. Gliding around models and audience, up and down the catwalk. I learn later that this is one man out of a collective behind the Instagram account @27b.6_. I have seen their wordless and voyeuristic portraits of pedestrians before. The camera lingering uncomfortably long till their subject(s) start to crack in a Warholian screen-test fashion. The account representative was invited by the artists themselves; though they may not have anticipated him stalking the catwalk as he did.

When a bright orange train of the London Overground passes the tracks and the models change back into their preferred city attire, a leftover bouffant hairstyle will be the only reminder that the audience has seen any art at all. We scurry back into London’s walls.

Introducing the press release is Nietzsche’s concept of eternal recurrence. A helplessly romantic push toward self-affirmation, it also stages life as an absurd play of recurring archetypes, charged with the history that shapes them. The collection pokes fun at the city’s self-seriousness and fashion’s obsession with the future. Clothes are read too quickly, identities too fixed. Designed away from the city, the garments return mischievous, repeating our absurd metropolitan codes, but askew.

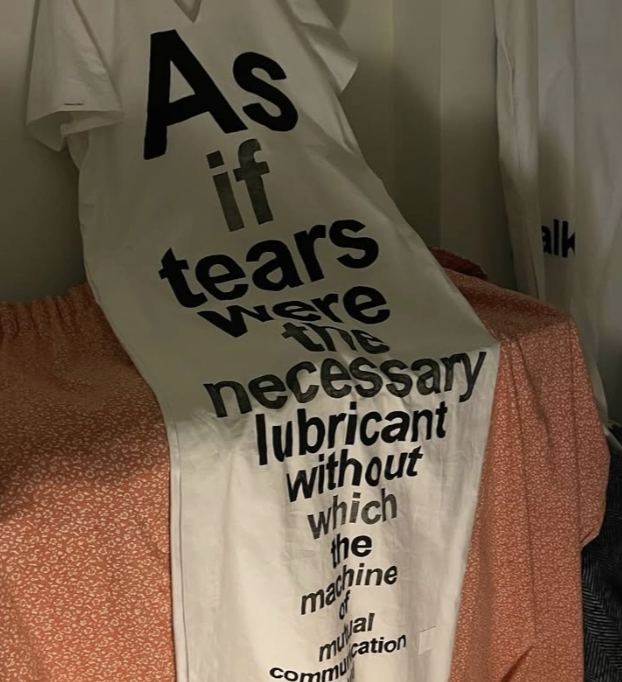

Mack is selling t-shirts on the table at the post-show reception. People are trying on the various prints, trying to find one that will fit their vibe. G puts on a tank top printed with a big “It” and M is happy with hers because the question mark at the end of the sentence will poke out of her cardigan in a nice manner. If the lines of text imitated the nonsense of optometric eye-tests, we are failing hard. The alphabet is to us only nice looking shapes, decorating a white backdrop.

Coming away from the show, I realise that I am wearing a '60s-vibe top and that my outfit is awfully charged. My outfit is the beige lint roller of all of history before me, and my '60s top is a ball of hair caught in its sticky tape.