On The Issywoodification Of Painting

Essay / 20 November 2025 / By: Timothée Shamalet

Issywoodification...a true generational turn towards the blurring of form, ala greenberg, for 2025. Where artists once tried to reduce form, achieve flatness, break down representation, they now aim for the affect of a camera rubbed with vaseline. While an analysis of causation will be undertaken elsewhere, in the meantime, our recently de-twinked Timothée Shamalet identifies the lack-luster impressions of such formal choices.

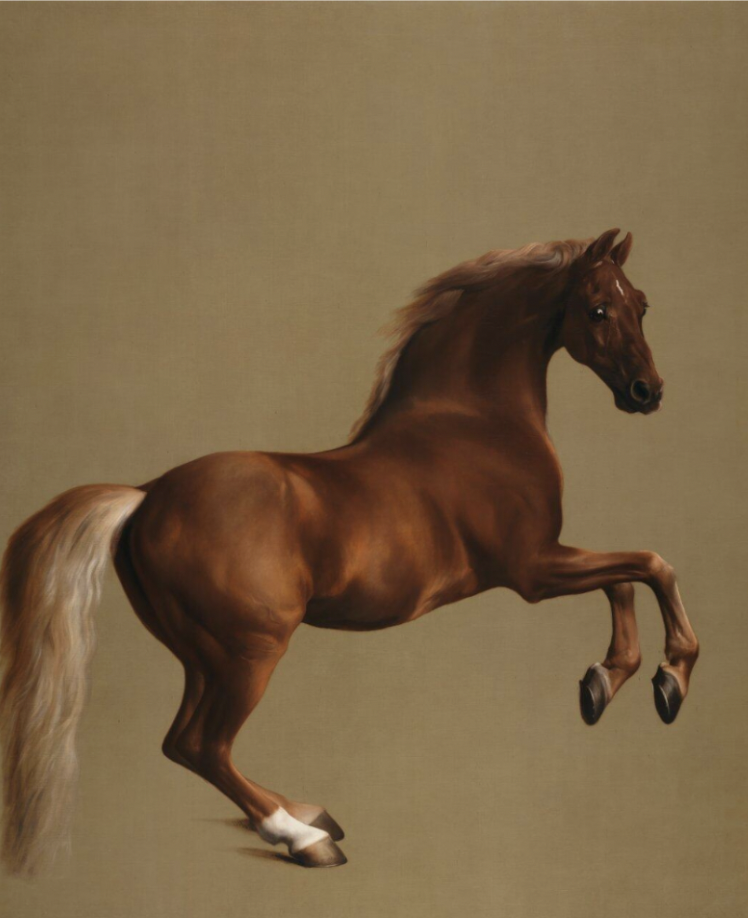

The best painting in the National Gallery is obviously George Stubbs’s Whistlejacket. A horse raised on hind legs, trunk shining by some dazzling light, against an entirely beige void – a perfection of realism in an expanse of absurd, estranging nothing. Conceptual iconography in 1762. It’s a shame Stubbs is remembered as a mere ‘equine painter’, but maybe that’s also kind of the point.

I was thinking of jackets, and maybe also horses, at Magic Bullet, Issy Wood’s survey exhibition currently on view at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavilion. Mainly while looking at My neck / my scapula (2025), an A3-ish oil on velvet work of a puffer jacket, structured but wearerless, framed like a classical bust. In the work, and in the room, there’s a notional toplight, but the reflections behave inconsistently. Instead of a shadow within the empty collar, Wood has painted thick lime green. The material is taught around the button poppers, our phantom model’s frame bulging the garment with their very legend. We are the hollow men indeed.

It’s just a coat, dickhead. But it’s a brilliant painting. Partly because the rest of the works here are mildly terrible. Wait, no. There’s also a pair of supersized dentures painted like the Elgin marbles, fine. Also, one work that looks like a flower - drooping low, creases accentuated like the tendons of a hand - stigmata shining like kitchen knives, but also the aliens from that film Arrival.

But back to the point: rooms upon rooms of unquestioning ugliness. D1NNER (2025) stages a kind of post-Carrollian tea party (‘Have always been fond of him’, noted Vladimir Nabokov in Strong Opinions. ‘One would like to have filmed his picnics’; if only Wood were so risky as to engage two of history’s great quasi-nonces) but for whom? Floral teapots, cups and dishes line up across an unattended, almost depthless frame – neither synecdochic nor particularly expressive, they evoke little that’s felt and reveal nothing. Crisis Is (2020) – continuing Wood’s distinctly Y2Kish fixation on twentieth-century cars – is part car-dealership-website-ad as AI-interpreted in the style of Philip Guston, part Lana Del Rey music video mood board. Paintings that just hope you’re thinking what they’re thinking. Wood’s recent portrait of Charli xcx for Vanity Fair postdates the exhibition, but in its ability to capture nothing that we don’t already know about the pop idol from pre-existing footage, it would have done well here.

Wood has a lot to answer for: her style – tight crops, photo-similar faces, kitsch Disneyfication, bathetic scenarios, darkened peripheries like early-Instagram vignette filters – has (to her credit) become ubiquitous in recent painting and image-making. In their homage to earlier image technologies – namely photographic film and notionally cinematic images – they reek of nostalgia. This is all Wood’s ‘hyper-modern visual language’ as per Schinkel’s intro text, a useful reminder of how anything that looks bad – in this case, paintings with the colour palate of Ravensburger jigsaw puzzles or the Ticket to Ride board game – can be reframed as a branding communication system. Schinkel Pavilion is in many ways the perfect site for this, a place benefitting from the sheer vibes of its late 60s German oldness, but with worse lighting.

[Intermission: If at this point you’re struggling with this piece, a reminder that many good painters are still out there – Hayv Kahraman, Nicole Eisenman, R. H. Quaytman, Justin Fitzpatrick, even Julie Mehretu!]

It’s also what career ArtForumer Barry Schwabsky calls ‘perverted realism’, with Wood as a figurehead for a cohort of ‘chromatically dark’ painters evincing a ‘pragmatic apprehension of the incalculable multiplicity of threats stemming from any number of apparently unrelated but equally unavoidable conditions’. Over in good old Londinium, you’ll find it everywhere: Lukasz Stoklosa’s recent show at Rose Easton, which seemed to think the gothic amounts mainly to a spooky mood; a second show at Soft Opening by Shannon Cartier Lucy who, like Chloe Wise, appears to think skin-shine makes a portrait interesting; don’t get me started on Joseph Yaeger’s deflowering of the new Modern Art space. Though, at least Yaeger’s actually look like old films.

Schwabsky cites Michaël Borremans as a forebear of this ‘perverted realism’. Ask yourself, though, would any of the cohort’s proponents be capable of anything like his Fire from the Sun (Four Figures) (2017)? Maybe that’s unfair, maybe they’re just young – or so I hear their gallerists call out from the back, seemingly unsatisfied with the volume of canvases they’re slinging. But nonetheless is it so bad to want it all to be more, well, actually perverted? Wood’s formal ‘perversions’ and autofictional arrangements obscure any real deviance or depravity up for grabs. Instead, we have bunny rabbits painted onto the backs of guitars and muscle tissue depicted in a state neither of preservation nor violent exposure. The grid-pattern in Rough Facetime Study(2025), a bang-for-your-buck technique shared by a contemporary like Louise Giovanelli, makes a briefly perplexing puzzle of the work’s subjects: some bracelet pendants and a porcelain cattle figurine. Are these really the dark recesses of the mind, the memory, or the lived experience they resemble? If Wood & Co’s works are facing the present world’s ‘incalculable multiplicity of threats’, then why are they so flat, so quiet, so fugitive? It’s certainly insufficient to be content with such bland nihilism; art should reach into the dark, not just gawp at it. Reminder: John Berger said that all art reflects its times (what a downgrade today’s public art intellectuals are.

Maybe it’d be better if Wood only did coats. Maybe a whole exhibition of one would work a treat; maybe even a whole career, like Peter Dreher for the Vinted era. (Much the same could be said of Giovanelli and satin shirts.) If Stubbs is the greatest of all horse painters, then Issy Wood will, with any luck, be remembered as champion of puffer jackets.